finding Siyu

The speedboat carved through the turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean, its hull slapping against waves that caught the East African sun like scattered coins. My three months’ worth of travel gear – that embarrassing weight of modern comfort I couldn’t afford to forsake, all stuffed into a single suitcase – sat at the bow like ballast, keeping us level as we approached Lamu. Squinting in the bright midday sun, I watched the town materialize from heat haze: whitewashed houses pressed shoulder to shoulder, their slanted dark red roofs punctuated by slender minarets jutting toward a cloudless sky. I noticed groups of people shuffling along the long corniche, but any sound of human life was swallowed by the rumbling engine of my boat.

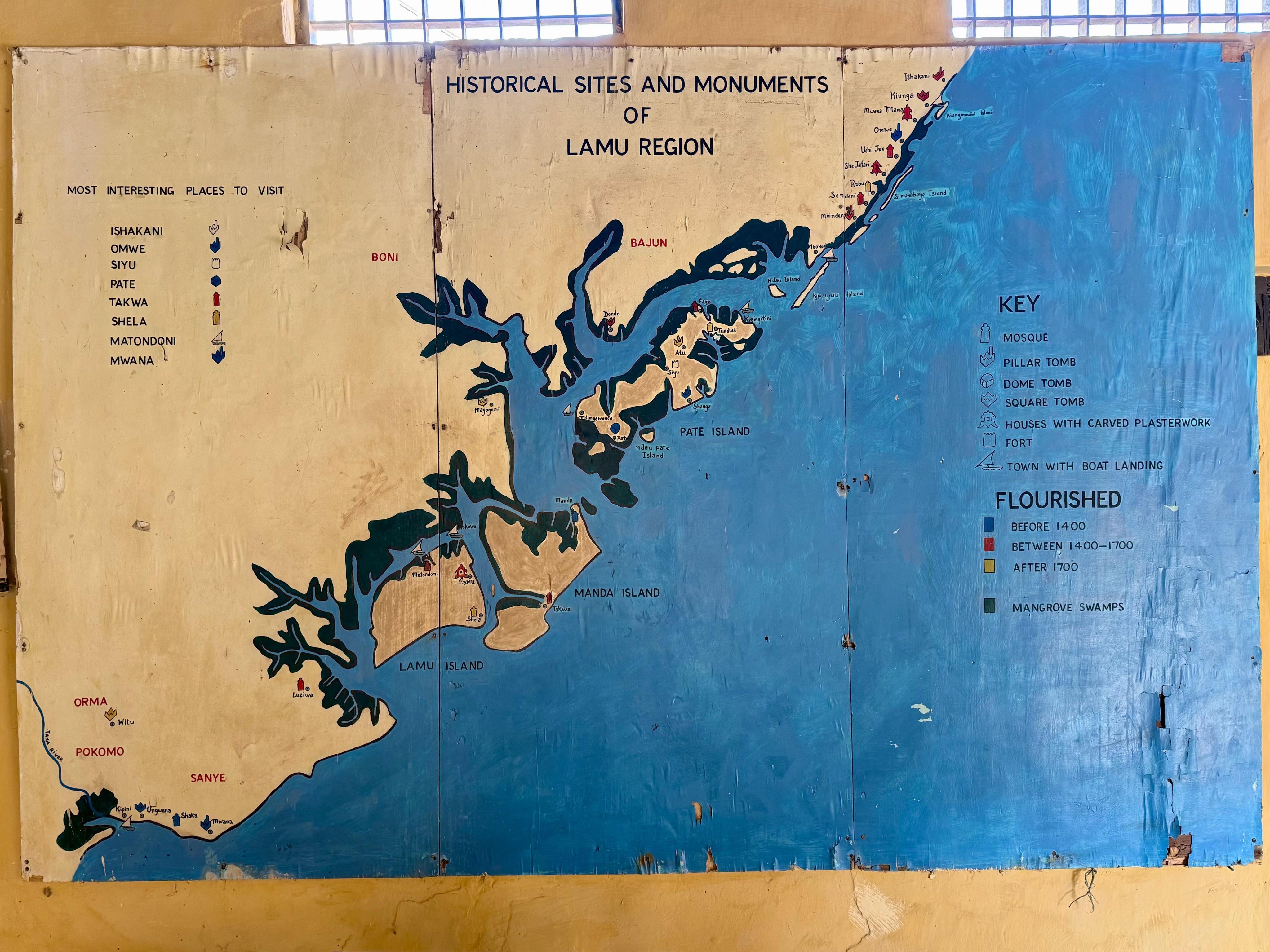

Lamu sits a few degrees south of the equator on Kenya’s east coast, part of an archipelago that once formed the heart of the Swahili trading world: a string of port towns bound by Islam, the Swahili language, and centuries of monsoon winds that carried wooden dhows between eastern Africa and Arabia. I’d flown in during the morning on a propeller plane from Nairobi, having slept through the view of Mount Kilimanjaro outside my window. The airstrip I arrived at was on Manda Island, across a short strait from Lamu to the east, making the final leg of every trip here a mandatory boat ride. As soon as I stepped out of the terminal building, I was immediately surrounded by captains offering passage across the strait. I negotiated a fare and found myself the only lone traveler heading over without prior arrangements. However, a private boat for double the price of a shared fare didn’t seem like a bad deal.

As we reached Lamu’s narrow concrete pier, chaos orchestrated itself into efficiency. Before I could worry about my footing as I got up to disembark, hands had already lifted me to solid ground. My suitcase appeared beside me before I realized, as if by magic. Ill-prepared for the exact change, I handed over my 1000 Kenyan shilling to the captain. He took the bill and, with a swiftness that felt well-practiced, counted back a small wad of sweat-stained change. When I tried to protest, his colleagues at the pier spoke in his defense. “Karibu Kenya,” one of them said with a light-hearted smile and slight shrug that needed no translation: Welcome to Kenya. This is how things work here.

The extra shillings I’d grudgingly shelled out turned out to be quite worth it when the captain offered to haul my suitcase through Lamu’s narrow alleys towards my guesthouse. The old town’s alleys were barely wide enough for two people to pass without some apologetic (at least on my part) eye contact or shoulder rubbing. Since there are no cars on the island, save for the fabled one ambulance and one firefighter which I never saw, donkeys claimed the right of way everywhere. Their droppings, however, remained where they fell. The ground was dotted sporadically with unattended donkey dung until the next rains arrived to sweep them away to the nearby drain. For now, it meant constantly watching my footing.

We finally reached the guesthouse, a tall, three-story traditional structure that felt higher as I looked up from the narrow alleyway, hemmed in by buildings on all sides. The captain set down my suitcase with me and bid goodbye with a wink, reminding me to book him for a boat trip, a sunset cruise, or just anything that a tourist ought to be doing when they visit Lamu.

Lamu’s draw, after all, isn’t new. Since the 1970s, when backpackers dubbed it the “Kathmandu of Africa,” the archipelago has attracted waves of travelers: first hippies seeking unspoiled coastlines, then bohemians drawn to its artistic heritage, and eventually the jet-setting wealthy who built grand villas along the beaches. The UNESCO-listed Lamu Town, with its labyrinthine alleys and centuries-old Swahili architecture, remains the cultural heart. But most upscale tourism has gravitated toward Shela Village, a few kilometers south and conveniently reachable by speedboats, where pristine white sand beaches stretch for miles and celebrity visitors like Princess Caroline of Monaco would slip in quietly between high seasons.

In recent years, though, the industry has stumbled. Security concerns related to extremist attacks on the mainland, particularly in Lamu County’s border regions, have cast a long shadow over the archipelago, despite the islands themselves remaining largely peaceful. Travel advisories warned tourists away. Hotels emptied. During my time at Lamu, I actually found there to be quite fewer visitors than I’d imagined: seaside restaurants with more staff than customers, shopkeepers who looked up hopefully at every passing figure. But I was here, and in this diminished season, that apparently counted for something for the captain. I politely took his number as he parted.

At the guesthouse, a young woman around my age named Maya came out to greet me. She was not particularly talkative, but had a calm, self-possessed air. She was my effective host during my stay; the owner was usually absent during the day, leaving Maya to take care of the house, manage arrivals and departures, and cook each morning meal.

After dropping my suitcase in my room, lunch became my most pressing need. I stepped back out, feeling the pull of the old town’s labyrinth. The narrow, twisting alleys seemed to follow no discernible order, but somehow they all funneled out onto the familiar seaside corniche where I’d just disembarked. At midday, I was spat out of the shadowy stone corridors into the blinding expanse of the seafront. It was the hub of activity, the only place where restaurants and ATMs clustered, so a natural anchor point for tourists like me.

The main reason I came to Lamu, though, wasn’t Lamu itself. It was a town about fifteen miles north in the archipelago: a town called Siyu. I’d stumbled upon it one night while aimlessly scrolling through Google Maps, the kind of geography lover’s doom-scrolling when you zoom in on random coastlines just to see what’s there. The name stopped me cold: Siyu. The same romanization as my Chinese name, 思宇.

Most Chinese people living abroad eventually pick an English name: something easier for foreign tongues, something that doesn’t need explanation at Starbucks or spelling out letter by letter over the phone to insurance companies. Twenty years ago it was names like Crystal, Cherry, and Jack; now it’s Vivian, Eric, and Yvonne, carefully chosen from lists of what sounds appropriately Western. But in my nearly ten years outside China, I’d never felt the need. Not because my name was easy to pronounce; it wasn’t. The first character, 思 (sī), requires you to make an “s” sound while positioning your tongue for “oo,” with lips retracted and unrounded. The second, 宇 (yǔ), asks for a slight dip in the tone preceding a carefully controlled rise, all the while trying to pronounce the sound of “ee” but with lips rounded and full. Together, they mean “thinking of the universe” or “contemplating space,” the kind of poetic construction Chinese parents love.

None of that mattered outside China. What I got was “See-you”, flat, toneless, convenient. What I got was “See you later, Siyu!” delivered with the proud grin of someone who’d just discovered wordplay. I’ve learned to perfect my patient smile for this joke, deployed it in a dozen countries, in so many languages that I have lost count. The pun followed me like a shadow I’d learned not to fight. But here, on a map of the Kenyan coast, was an island that shared my flattened name. It felt like a sign, or at least a coincidence too good to ignore. So I’d built my trip around it, a pilgrimage to a place that bore my name, even if neither of us knew why.

After my filling lunch of pilaf with lamb, I spent that first afternoon in Lamu wandering around. I chose turns at random, following whichever alley looked most promising. The town revealed itself in fragments: a hidden plaque with names of ports far on the Persian Gulf, an office with elaborately carved doors advertising consultations for marriage problems, a cafe with too many modern art pieces it felt like a touristy trap lifted out of Marrakesh. I passed one intersection three times before I realized it, but nobody seemed to notice or care.

The next morning, I went back to the corniche for breakfast. The sun was already brutal at eight., bouncing off the white walls and turning the strait into a sheet of hammered silver. I’d just ordered chai and mandazi from a corner cafe when a man appeared beside my table.

“Jambo,” he said, smiling. “You are going somewhere today?”

The man was maybe forty, compact and shorter than me. He wore a shirt identifying him as an official guide, though the fabric was so faded and worn it seemed like he might choose to wear it every single day. Before I could say anything, he produced a laminated ID card dangling from a lanyard around his neck, holding it up at eye level to me. His name was Abu.

“Maybe,” I said.

“Where you want to go? Shela beach? Manda ruins? I can arrange a very good price.”

“Actually,” I said, “I want to go to Siyu.”

His eyebrows lifted. “Siyu? Why Siyu?”

“Well, I’m Siyu,” I said, and immediately realized how stupid that might have sounded without context. “I mean, it’s my name. In Chinese.”

But Abu’s face lit up “Ah! You know about the Chinese? The sailors?”

I did, sort of. I’d done my research before coming: the stories about Admiral Zheng He’s fleet, those massive Ming Dynasty treasure ships that had sailed these waters six centuries ago. One ship, according to legend, had wrecked somewhere near the island. The Chinese sailors had supposedly swum ashore, married local women, and dissolved into the Swahili gene pool. A few years back, Chinese archaeologists had arrived with film crews and DNA test kits. They’d confirmed that many residents on the island actually had Chinese blood. One of them was a girl named Mwamaka Sharifu. I’d read about her story in a Xinhua News article that popped up when I Googled her name: Mwamaka was beaming at the camera in a bright colored Manchurian costume, the caption celebrating her government scholarship to study traditional Chinese medicine in Beijing.

“I have family there,” Abu said, pulling out a chair without waiting for invitation. “In Siyu. I can take you. We stay one night, two nights. I show you everything, the fort, the old mosques, the beach where the Chinese came.”

We decided to take the local boat that afternoon. Abu said it would leave around 2pm, which in practice meant sometime between 3 and 5. While we waited at Cafe Mangrove, nursing lukewarm Coca-Colas and watching the strait shimmer in the heat, Abu suddenly stood up.

“Wait here,” he said. “I have an idea.”

He disappeared into the maze of alleys. I sat there wondering if this was the moment he’d vanish with my deposit, but ten minutes later he returned with a middle-aged man trailing behind him. Thin, maybe in his mid-fifties, wearing a shirt that had seen better days.

“This is Mwamaka’s brother,” Abu announced, too loudly, like he was presenting a prize. “The one with Chinese blood.”

The brother looked at me with an expression I couldn’t quite read. Not intimidating, but not eager either. More like someone who’d done this before and knew how it would go. Abu launched into enthusiastic interviews, asking questions the brother answered in short Swahili phrases that Abu stretched into longer explanations. Did he know about his Chinese ancestry? Yes, of course. Had he met other Chinese visitors? A few. Did he know anything about the Chinese here? A shrug. I sat there feeling like an anthropologist who’d accidentally become the subject of observation. The whole meeting felt like a rehearsed reality, Abu’s questions, the brother’s cryptic responses, and the way they’d positioned themselves for what came next.

“You want photo?” Abu asked, though it wasn’t really a question.

The brother was already sitting beside me, Abu already lifting my phone from the table. I handed over some bills afterward, an amount that in retrospect felt both too much and not enough. The brother pocketed the money without counting it and left with a nod that might have been gratitude, or might have been goodbye, or might have been nothing at all.

After he’d gone, Abu leaned back in his chair. “Life is very difficult here now,” he said quietly, watching the brother disappear into the alleys. He didn’t elaborate, but he didn’t need to. I’d read about Lamu’s other crisis before coming: the heroin problem that had taken root in some neighborhoods with names like Kashmir and Kandahar. Men caught between collapsed fishing industries, a tourism sector gutted by security concerns, and a government that seemed indifferent to the coast’s economic survival. The drug trade flowed through the same maritime routes that once carried spices and ivory, but now offered a different kind of escape. Sitting there with my phone full of photos, I tried not to think too much about where my money would end up. But the thought lingered anyway.

“The boat will leave soon,” Abu said, checking his phone. “we should get on now to get a good spot.”

The boat was a weathered wooden dhow with a small outboard motor, already scattered with some early passengers who’d claimed the best positions. I found a spot near the stern and sat down on my backpack, letting one leg dangle over the side where the water lapped against the hull.

Then we waited. And waited. More passengers arrived with bundles of goods: sacks of clothes, electric appliances in bulky boxes, and bagfuls of food. An hour passed. The afternoon sun beat down on the exposed deck. Finally, around 4 p.m., the captain decided we had enough passengers, or enough cargo, or simply that enough time had passed. Pole pole, as people often say in Swahili. Slowly, slowly.

By the time we pushed off, every surface held a body or a bundle. I was wedged between my backpack and a sack of something that smelled vaguely of cardboard and salt. The engine roared to life, drowning out conversation, and we began the slow chug north along the coast.

A woman in her twenties sat across from me, alone, watching out to the sea and occasionally scrolling on her phone. She traveled light, with just a small backpack, no shopping bags or bulging suitcases. After about twenty minutes, when the engine noise settled into a steady drone, she leaned forward.

“Where are you going to?” she asked, her voice tentative but clear.

“Siyu,” I said. “You?”

“Kizingitini. I teach there. Primary school.”

Kizingitini is a town on the same island as Siyu, about a half hour of motorbike ride away. She’d been posted by the government, she explained. Young teachers get assigned to remote schools, no choice in the matter. She’d been there six months. She just spent her vacation back home in central Kenya, and was coming back to teach. She asked where I was from. When I said China, her face brightened slightly.

“Some teachers from my last school went to China,” she said. “An exchange program. They came back and said it was very developed, very different.” She paused, then added more quietly, “I’m trying to apply for a scholarship. To study there.”

I asked what she wanted to study. Education, she said, or maybe technology. Something that would get her off these islands, off these slow boats, into a place where time moved at a different speed. We exchanged WhatsApp numbers before disembarking. She wrote hers carefully in my phone, then sent herself a message so she’d have mine. “If you have time for tea,” she said, though we both knew I wouldn’t.

The boat landed at the small seaside settlement of Mtanga Wanda as the sun began its descent, turning the water from turquoise to a deeper, quieter blue. Abu negotiated with a motorcycle driver waiting at the small pier, and within minutes the three of us became a single precarious organism, weaving through red dust paths toward Pate village, where we’d spend the night.

Pate Island holds several settlements, but three carry historical weight: the namesake Pate, Shanga, and then Siyu. These were once-significant Swahili trading towns, their fortunes rising and falling with the tides of Indian Ocean trade.

We arrived in Pate as the last light was fading. The village felt much smaller than Lamu, quieter, the alleys narrower if that was even possible. Coral stone houses pressed close together, their walls darkened by age and weather. A few men sat on benches outside their houses, watching us pass with mild curiosity. The motorcycle dropped us in a small clearing, not quite a square, just a widening of the path where several alleys converged. Abu gestured for me to follow and headed down one of the passages.

We walked through a narrow doorway into a room so dark I stopped at the threshold, waiting for my eyes to adjust. It took a full minute before I could make out the interior: a small bedroom with coral stone walls, a wooden bed frame strung with woven plant fibers, and an old lady whom Abu introduced as his grandmother. She was sitting on the edge of the bed, her legs dangling above the earthen floor. A small charcoal stove burned beside the bed, filling the room with smoke and heat.

“My grandmother feels cold,” Abu explained, though the temperature outside was still hovering around thirty degrees.

His aunt appeared from the doorway and handed us tin cups of heavily sugared tea. Abu negotiated in Swahili with his aunt about dinner arrangements, quick exchanges I could only follow the gist. My ear was still more attuned to slow-paced and clearly pronounced speech, and their coastal dialect had rhythms and words I’d never encountered in textbooks.

After a few minutes, Abu turned to me. “You will eat dinner here with my family.” We stepped back into the late afternoon light, and Abu summoned two local boys who materialized as if they’d been waiting. They walked us through the village to see tombs: Islamic ones, Abu explained to me, though they looked like coral stone mounds half-reclaimed by vegetation and scattered with plastic bottles and food wrappers. The boys offered terse and vague commentaries. At some point they ran out of things to say, and we just walked in silence along narrow paths beneath banana trees, their broad leaves filtering the dimming sunlight into green shadows.

We stopped at a small mosque as the call to prayer began. I waited outside while Abu and the boys went in, watching the last light drain from the sky. When they emerged again, Abu and I parted ways with the two boys and the two of us headed back to the small clearing at the village center. We climbed to the second floor of Abu’s grandmother’s house, and waited for another hour while the women finished their prayers in private before they started cooking.

Dinner was spaghetti, a recurring pattern that I began to notice. In rural parts of East Africa, spaghetti often appears when hosting foreign guests, a gesture towards what the host imagines a guest might want. This version was sweet, loaded with sugar the way the tea had been, maybe another mark of hospitality. We began eating while sitting on the floor, and I quietly asked for a fork and knife after a few minutes. There was also rice, a mixed salad of tomatoes and onions, and two small fish the size of a palm fried until their skin had blackened and crisped.

Only the men ate. Abu’s aunt and grandmother stood watching from the doorway, occasionally refilling our plates. I debated whether to invite them to join us, wondering if offering would be respectful or presumptuous, and ended up saying nothing. When I announced I was full, I made sure to leave one fish untouched. No one touched the fish until I’d clearly finished.

After dinner, Abu walked me to his cousin’s house where I’d sleep. We shared a torchlight while we explored the space, since there was no electricity. The place had the hollow feeling of abandonment, dust on every surface, windows that didn’t quite close, a tank with water of uncertain age. Abu arranged for me to sleep in his cousin’s room, and went out to set up his mattress on the living room floor.

I’d forgotten my earplugs. Through the night, I listened to donkeys clattering past my window, their hooves on stone, their braying echoing through the narrow alleys, and sleep only came in fragments between their passages.

Needless to say, I woke early the next morning, gritty-eyed, unrested, almost as if the cluncking sound of donkey hooves was still echoing in my skull. We had breakfast at a small shop where an old man sold fried samosas through a window already opaque with oil. We sat on plastic chairs looking through windows thick with spider webs. After we finished eating, Abu negotiated with a motorbike driver for the entire day while I sipped overly sweet tea. The plan was to go to Shanga first, then Siyu, then back to Mtangawanda to look for an afternoon boat to Lamu.

The ride to Shanga took us on bumpy roads into the island’s interior. The red dust path cut through scrubland where scattered signs of human civilization appeared and disappeared.

We arrived in Shanga and waited under a massive baobab tree while Abu asked around for people to show us around. Eventually two elders appeared. Abu explained our purpose, after which the elders exchanged glances and then nodded. We were led through a scrub forest towards the coast while we were fed repositories of the island’s unofficial history, the kind passed down through generations of telling rather than writing, shaped and reshaped by each new teller until the truth became less important than the shape of the story itself. We stopped frequently at weathered tombstones half-hidden in vegetation, their inscriptions eaten away by salt air and centuries.

“Very old,” the taller one kept saying, gesturing at inscriptions I couldn’t make out. “From the time of the sultans. Very important people.”

When we finally reached the shore, a stretch of mud and mangrove roots indistinguishable from every other stretch of coastline we’d passed, the taller elder stopped and turned to face me with theatrical solemnity.

“This is where the Chinese sailors came ashore,” he announced, his arm sweeping across the mangroves as if presenting evidence. “When their ship broke on the rocks. They swam here, to this exact place. And Shanga” he paused for emphasis, “this name comes from Shanghai. Your ancestors, they named it after their home city.”

I knew this was almost certainly wrong. Shanghai hadn’t been a significant port during the Ming Dynasty, just a minor fishing town, nothing that would lodge itself in a sailor’s memory strongly enough to name a new settlement after it. The story was too neat, too convenient, the kind of etymology that works emotionally but not historically. But the elder’s conviction in this connection was so genuine and carefully maintained, that I only found myself nodding.

“Very interesting,” I said, which was true, if not in the way he thought.

We continued our walk through the mangroves, our feet squelching in black mud that sucked at our shoes with each step. The elder pointed out various features: a particular bend in the channel where the ship supposedly foundered, a clearing where the sailors had built their first shelter, a depression in the ground that was definitely, absolutely a well they’d dug.

I thought about all the versions of this story that must exist, Chinese archaeologists arriving with their DNA tests and government funding, seeking proof of ancient connections; tourists like me, drawn by coincidence and curiosity; locals who’d refined the narrative over years of retelling, shaping it to match what visitors wanted to hear. Each group finding what they came looking for, each leaving satisfied that they’d touched something true.

After about half an hour, we said goodbye to the two elders at the edge of the village. I handed over the agreed-upon shillings, plus a little extra that the elders accepted with dignified nods. As we climbed back onto the motorbike, heading toward Siyu, I realized I was no closer to understanding why the island bore my name. But perhaps that was the point. Perhaps the search itself was what mattered, not the answer.

The ride to Siyu took twenty minutes along a smoother path. The town revealed itself gradually, first a huge sign of the name, then a scattering of houses, then signs of permanence: a small hospital with peeling paint, a primary school with children’s voices drifting through open windows, shops selling necessities rather than souvenirs. Siyu was more developed Shanga, more inhabited, less frozen in time.

The main thing to visit was Siyu Fort, a construction that dominated the town’s image similar to the pictures that I found when I looked it up: a massive coral stone structure with walls thick enough to withstand cannon fire. It had been built in the early 19th century, when Siyu was powerful enough to resist Omani sultans and rival Swahili city-states, when this small island commanded enough wealth and strategic importance to warrant such defenses.

The fort keeper materialized as soon as we approached, as if he’d been waiting. He was elderly, moving with the careful deliberation of someone whose joints no longer cooperated fully. He fumbled through a bare anteroom to fetch a guest book, its pages dog-eared and sparse.

“Please, sign it.” he said, presenting it with ceremony.

I flipped through the pages. Two or three visitors per week, sometimes less. A solo traveler from Germany. A couple from France. A person from Port Townsend, Washington, which felt impossibly random and close to where I live in the US. I added my name, deliberately adding my Chinese characters, and wrote “Seattle” in the “From” section.

The fort keeper led us through the structure, pointing out features that had long since lost their context, arrow slits for weapons that no longer existed, rooms for functions no longer performed. After the fort, we walked through the town to see other sites: a mosque with an intricately carved door, tombstones of forgotten notables, a well that supposedly predated everything else.

Finally, I asked about the name. Why Siyu? Where did it come from?

The fort keeper shrugged. “Very old name. From a long time ago.”

By the time we returned to Mtanga Wanda, it was already in the afternoon and the passenger boat had left. At the port, there was only a larger vessel that had just finished transporting bags of cement from Lamu to here. The crew was working to clean it, hauling buckets of seawater onto the deck and scrubbing away the gray dust that coated every surface. The captain generously agreed to take us back for free.

The return journey took two hours, but felt much faster. Unlike the cramped ride over, this boat had space. I found a relatively clean section of deck and lay flat, using my backpack as a pillow, watching the sky shift to dimmer but more saturated shades of blue as we motored south. The engine’s rhythmic drone worked like a sedative. I felt my eyes grow heavy, then close.

Back in Lamu, the boat docked just as the evening call to prayer began echoing across the waterfront. Abu reminded me about his tip as we were walking away from the pier and getting ready to part ways. I handed over some extra bills. He thanked me, told me to enjoy the rest of my time in Lamu, and walked back toward the corniche where other captains and guides would be gathering as boats came to shore.

The guesthouse was quiet when I arrived, feeling almost empty. I dropped my backpack in my room, washed the red dust from my hands and face, and climbed the narrow stairs to the rooftop. Maya was there, hanging laundry, sheets and pillowcases snapping in the wind like small sails.

“Did you find what you were looking for?” she asked without looking up, her hands moving with practiced efficiency, pinning corners against the breeze.

“I found Siyu,” I said, jokingly.

She smiled at the clothesline. “So was it the same as what you were looking for?”

I thought about it, about the Shanghai story that wasn’t true, about all the elders with their competing etymologies, each one certain, none quite convincing.

Maybe we were all right. Maybe we were all wrong. Maybe it didn’t matter. In the end, a name is just a sound we’ve agreed that means something, even when we can’t agree on what. My name just happened to match an island’s, not because of shipwrecks or some cosmic significance, but because somewhere, sometime, people decided to call a place Siyu, and my parents decided to call me 思宇, and the funny English romanization made them look the same. The island kept its mystery. I kept my name. And that somehow felt like enough.

“Maybe there was nothing to look for,” I said finally. “Or maybe I was looking for the wrong thing.”

Maya finished with the last sheet and picked up her empty bucket. We stood there facing west, where the sun was dissolving into the Indian Ocean. The sky had turned that particular shade of equatorial orange, pure, saturated, almost unreal. The water doubled it back. Along the seafront below, lights began flickering on. The muezzins’ calls from different mosques wove together, less like music than architecture made of sound.

“Beautiful,” Maya said simply.

“Yes.”

A dhow sailed past, its white sail catching the orange light. The air carried charcoal smoke and salt. Below us, voices called across alleys, dishes clattered, a donkey brayed somewhere in the stone maze. The orange deepened to rose, then to purple. We stood watching as the color slowly drained from the sky, the strait turning from silver to pewter, the whitewashed houses beginning to glow against the dimming light.